|

1. Overview

|

Name: |

Oostergo |

|

Delimitation: |

Oostergo is bordered by

the Wadden Sea in the north, and by the eastern Middlezee dike in

the west. The Lauwerszee and river Lauwers form the eastern border.

The southern border runs over the Boorne dike to Oldeboorn and then

along the Stroobos canal. |

|

Size: |

around

360 km˛ |

|

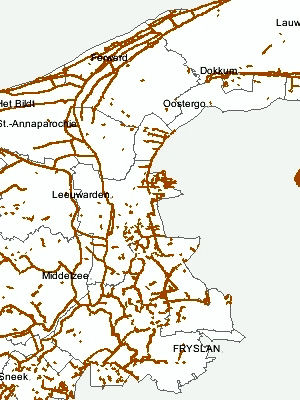

Location

- map: |

Province

of Fryslân, the Netherlandsany |

|

Origin

of name: |

The north part of

Fryslân was bisected by the Middel Sea. The island on the east side

is Oostergo (Oost means east). |

|

Relationship/similarities

with other cultural entities: |

Related

to Westergo, Middelzee and Lauwers |

|

Characteristic

elements and ensembles: |

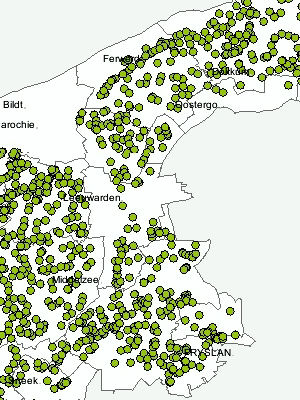

Open area with salt

marsh embankments on which there were mound (terp) villages at 2-3

kilometre intervals. Very open landscape; dwelling mounds in curved

rows, structures of water ways, (former) seawalls and locks;

historic field patterns; natural water courses, medieval town

centres and village like Leeuwarden and Dokkum, historic farm

buildings, stone houses (zaalstinsen). |

2. Geology and geography

2.1 General

The Oostergo landscape was formed in the Holocene period, (the

current geological period). Around the higher sandy area of the Frisian

Wouden and the peat moors of the Lage Midden a broad band of clay was

deposited, measuring up to 10k wide in the north, and gradually narrowing

towards the south. The river Boorne, which rises in the sand and peat

areas of south-east Friesland, formerly turned northward to the west of

Aldeboarn and discharged into the Wadden Sea.

|

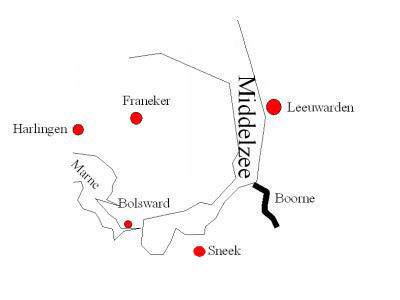

| Middelzee with river Boorne |

The Oostergo

landscape is bordered on two sides by large estuaries: the Boorne (Middelzee)

and the Lauwers (Lauwerszee). Marine clay was deposited along the inlets.

The ridge thus formed by the sea is now a salt marsh embankment.

2.2 Present landscape

Oostergo has an open landscape with high dikes offering protection

from the sea. The accretion of land at the coast is a continuing natural

process.

|

|

| Photo: Accretion of land outside

the dykes |

Dykes in Oostergo |

3. Landscape and settlement history

3.1 Prehistoric and Medieval Times

The earliest permanent settlement was around 600 BC, when people

moved into the coastal area from the Drenthe plateau. The first

inhabitants settled on the highest points: the salt marsh embankments and

high banks of the streams. Initially they lived directly on the

ground-surface of the embankments. Over time however, as sea level rose

and flooding increased, the dwellings had to be raised. Mounds were

created from whatever came to hand; household refuse, manure, clay and

turf, and gradually the first dwelling mounds (terpen or wierden) were

constructed from c. 500 BC. The place-name “wier(de)” also means an

artificially raised dwelling place. A number of terp villages in Oostergo

have the suffix -wier(de), such as Metslawier, Niawier and Poppingawier.

Initially the terps accommodated individual dwellings, but over time they

grew together into raised villages.

|

|

| Dwelling mound in Oostergo |

Terp village Nijewier |

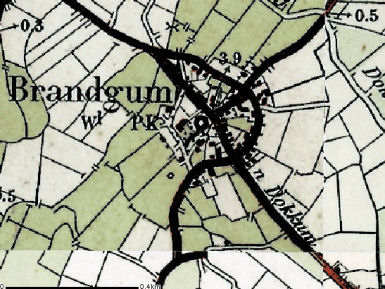

The oldest

form of village terp consisted of round, separate terps with plots

radiating out from them, and sometimes a ditch around the foot of the

mound. Examples of such round terps include Foudgum, Hogebeintum, Brantgum

and Oostrum.

|

|

| Round terp village Brandgum |

Photo: Village Hogebeintum |

From around

700 – 800 AD a different kind of terp developed as a trading terp. At this

date the Frisian coast was at the crossroads of several important European

trade routes, so trade flourished. The trading terps were largely found on

the banks of a stream, just behind the coast: examples include Aldeboarn

on the Boorne and the old centres of Leeuwarden and Dokkum on either side

of the Dokkumer Ee. This type of terp had an elongated shape with

buildings along a central road.

|

| Map of Aldeboarn (Oldebbrn) |

3.2 Early Modern Times

The construction of a continuous sea dike around Oostergo stopped

most of the regular flooding of the land, so it was no longer necessary to

live solely on the high salt marsh ridges. From around the 12th century it

was also possible to live on the lower-lying salt marsh plains. The arable

fields were still on the higher embankments and the flanks of the terps.

The poorer, wetter land around the terp was used for pasture and hayfields.

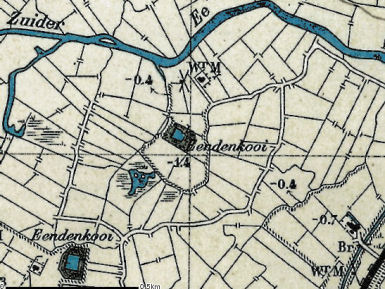

In the lowest-lying areas, south of Anjum, there are duck decoys,

sometimes as many as four close together.

The continuous dike along the Middelzee and the Wadden Sea was probably

built around 1100 AD. It ran from Deersum via Irnsum, Roordahuizen,

Leeuwarden, Stiens, Holwerd, Wierum and Oostmahorn to Engwierum. If salt

marshes outside the dikes were silted up sufficiently, they were sometimes

also reclaimed and farmed. Once a new dike was built further seawards, the

old dike lost its purpose, and was often dug out. Monasteries established

in the area from 1100 onwards played an active role in dike building and

land reclamation in Oostergo, particularly Mariëngaarde near Hallum and

the Gerkes monastery in the Lauwerszee area.

|

|

| Duck decoys (Eendenkoois) in

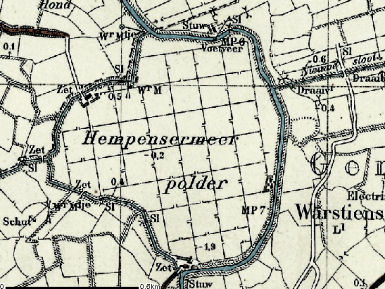

Oostergo |

Hempensermeer Polder |

In addition to reclaiming land from the sea, land was also reclaimed in

Oostergo by drying out pools. There are three such small drained pools

south of Leeuwarden: the Hempensermeer and Greate Wergeastermeer polders

and the Lytse Mar polder east of Wergea. These polders were pumped dry in

the 17th and 18th centuries and are characterised by a very regular

rectangular fieldscape that is typical of reclaimed land.

Initially surplus water from the adjoining land in Oostergo was

discharged into the Middelzee. After the polders were made, a quay was

built on the Oostergo side along the Zwette, the ditch marking the border

between Oostergo and Westergo. This made drainage toward the Middelzee

impossible, so the drainage point was moved to Dokkum. A number of

waterways, such as the Huijumervaart and the Heerenwegstervaart, were dug

to solve the drainage problem. Where a stream or waterway discharged into

the sea a discharging sluice or zijl was built in the dike. The

reclamation of the Bildt meant that an important Oostergo sluice in Oude

Leije had to be moved twice. The polder water has been discharged at

Nieuwe Bildtzijl since the 18th century.

In the medieval period peat was dug on a large scale in Oostergo to

extract salt. The dug areas have a distorted soil profile and are still

recognisable in the landscape as elongated lower lying areas, particularly

in De Kolken south of Anjum, and between Wetzens, Jouswier and Oostrum,

where large areas of peat were extracted. In addition to peat extraction,

clay was also taken in some areas to make bricks. Initially these were

used only to build monasteries and churches, but later they were also used

for noble houses, and later still for farms.

While agriculture was still the most important source of income, the

increase in trade meant the development of towns. Dokkum arose where the

Dokkumer Ee flowed into an inlet of the Lauwerszee: the present day

Dokkumer Grootdiep. Two terps were built on the northern side of the

watercourse which now form the centre of the town. In the 12th century the

Norbertine Bonifacius Abbey was built on the northern terp, which is now

the Markt. After the Reformation at the end of the 16th century the Abbey

was demolished. The veneration of Boniface, the missionary and bishop who

was murdered near Dokkum in 754, received a boost in 1925 when the St

Boniface Chapel and garden were built on the south side of the town.

Leeuwarden lies where the (Dokkumer) Ee once flowed into the Middelzee.

There are three terps in the centre of the town which formed the original

urban area: the Oldehove terp, and the terps at the level of the Kleine

and Grote Hoogstraat, which lay on either side of the Ee. From 1200 to

1500 the town expanded significantly, becoming the provincial capital in

1504. It was also significant that Leeuwarden became the seat of the

stadhouder of Friesland. From 1584 to 1747 the stadhouders lived in the

court on the Hofplein.

|

| Photo: Stadhouder Hof in

Leeuwarden |

3.3

Modern Times

In the 19th century Leeuwarden became an increasingly important

road and rail hub. As a result it enjoyed modest industrial growth, with

the emphasis on the agricultural sector. New districts were created

outside the historic centre for the growing population.

Waterways were still the major transport routes in Friesland until well

into the 19th century. Streams and rivers had been used to transport goods

since the earliest occupation of the area. Many of these small waterways

were later straightened, or made into canals. A number of major canals

were created for heavier traffic. Most of these were originally natural

watercourses which were made into boat canals in the mid-17th century.

|

| Old and recent waterways in

Oostergo |

This involved

widening and deepening the channel and creating towpaths. Large-scale

commercial levelling works between 1840 and 1945 left practically none of

the dwelling mounds intact. The fertile soil from the mounds was used to

fertilise agricultural areas elsewhere. To transport the soil the original

terp channel was dredged or a new one was dug, so that the terp was

connected to the network of major waterways in the area. Oostergo also has

a network of roads. The roads traditionally follow the course of the old

dikes over the banks, beside gullies and streams, as these were the

highest and driest parts in the area.

Land acquisition was tackled systematically from the start of the 19th

century. Pits were dug in the salt marsh to catch the silt and mud-flat

sediment. Once they were full the silt was spread over the marsh, and the

process was repeated until the marsh was high enough above water-level.

Large-scale reclamation work was undertaken in 1935, during the time of

mass unemployment. A method was adopted which was then common practice in

Schleswig Holstein, and seems to have come directly from Vierlingh.

Brushwood fences were made to enclose “sediment fields” of 400 by 400

metres. Channels were dug every five metres in these fields, and the

deposited silt was excavated twice a year and spread on the field. Each

field also had two major ditches parallel to the dike. All the channels

emptied into these major ditches, so that the sediment field was drained

at ebb tide and plants could take a good hold. The plants used to

encourage this development were mainly glasswort, salt-marsh grass and

cord grass.

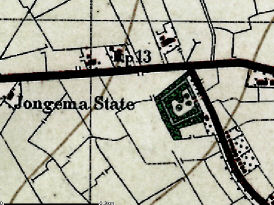

It is thought that there are no surviving mounds left in Oostergo that

were built for defensive stone houses (stinsen), except perhaps the mound

of the former Jongemastate in Rauwerd.

|

Mound of Jongemastate in Rauwerd |

|

There are also no surviving tower houses left in Oostergo. In the 14th and

15th centuries hall houses (zaalstinsen) were also built, which were more

comfortable to live in than the stone towers. From the 16th century

onwards the stone houses gradually lost their defensive role and became

largely status symbols; they were often converted into stately homes with

estates. Although many country estates in Oostergo were given the title “state”,

they were not all developed from the original stone stinsen. Fine estates

of gardens and forests were laid out around many of the stately houses in

the 17th and 18th centuries.

4. Modern development and planning

4.1 Land use

Oostergo is predominantly under grassland and maize used for livestock

farming. The coastal areas heavy marine clay is more suitable for potato

growing.

4.2 Settlement development

There are two large towns in Oostergo, Leeuwarden and Dokkum, both have

expanded since the Second World War and exert a great deal of influence on

their surroundings. As the provincial capital Leeuwarden has many of the

regional institutions such as hospitals, colleges, cultural institutions

and business activities. Locations for new build neighbourhoods are in the

south and east of the town. In the northern part development has already

taken place in the district 'Bullepolder'.

4.3 Industry and energy

Industry is largely agriculture-based. The harbour activities at Dokkum

are more of a tourist attraction. Leeuwarden is largely a service centre

and has no heavy industry.

4.4 Infrastructure

Leeuwarden is at the hub of water, road and rail routes. There is a

planned ring road on the west and southern part of the city of Leeuwarden.

A new road has also been built from Dokkum to Drachten, the Centrale Axis.

5. Legal and spatial planning aspects

The Legal and Spatial Planning Aspects are described here in a generalised

way, as they are relevant to all the entities in the province of Fryslan.

Because of the scale of the cultural entities (most cover more then one

municipality) the focus is on regional policy and management. However the

goals of regional policy and planning are taken into account by local

sector policy. The regional goals and strategies are formulated after

discussion with a wide range of sectors, stakeholders and organisations.

The regional spatial plan for the province of Fryslân, (the Streekplan),

is an important document in terms of integrated management of landscape

and heritage. This plan details the objectives for regional and local

policy, and issues relating to landscape and heritage

The provincial planning vision for North-East Fryslân centres on

exploiting and reinforcing of the special qualities of the area, to

provide a social and economic boost to the region. The construction of the

Central Axis will start to connect the region to the main road network,

and reinforce the central position of the regional town of Dokkum.

6. Vulnerabilities

6.1 Spatial planning

The open space, skyline and structure of the historical cities, towns and

villages are very vulnerable to ill informed planning for new housing and

industry. This is especially the case in and around Leeuwarden and on a

smaller scale in Dokkum.

|

| Photo: Village of Weidum |

6.2 Settlement

The growth in the population of the former terp villages often means

extending rather than developing in the existing residential areas.

Allowing new developments to blend in with their surroundings demands a

great deal of care and investment. Industrial estates are often built on

the fringes of the main urban areas. The construction of the Central Axis

will provide opportunities as well as threats. There are no surviving

mounds left in Oostergo that were built for defensive stone houses (stinsen),

or surviving tower houses.

6.3 Agriculture

The historic field pattern, natural watercourses and the historic farm

buildings are vulnerable due to agriculture developments. Many of the

smaller settlements that had been on mounds have already been lost to

agricultural improvements. In rural areas the province aims to combine

sustainable prospects for agriculture with a more extensive range of

activities and services. It is anticipated that agricultural production

will be scaled up considerably, particularly in the clay area. Continued

agricultural practices will disturb or destroy buried archaeological

deposits.

7. Potentials

7.1 Spatial planning

The proposed residential and industrial development should consider the

cultural heritage, both in terms of recording prior to development and

management of known sites. Within the historic core of the towns and

cities careful planning should protect the historic layout and surviving

buildings.

7.2 Settlement

Some of the historic settlements survive and these could be promoted for

tourism. The dispersed settlement pattern of small villages and farmsteads

have the potential to be promoted via tourism for their cultural heritage.

The histroic settlement patterns, now largely lost to modern agrculture

could be promoted via museums etc. Well designed conversions and

extensions can allow historic buildings to fulfull the demand for new

housing and small scale industrial uses.

7.3 Agriculture

Sustainable agriculture in relation to meadowland, migrating birds and

cultural historical elements contribute to the development of tourism.

There is potential for disused agricultural buildings to be used for new

housing, holiday accomodation or new small scale industrial enterprises

and for development of locally specific brands of agricultural products.

7.4 Tourism

The area has clear potential for landscape and cultural history tourism.

Using historic buildings and farmhouses for accomodation, old paths for

walking and cycling and old water ways for pleasure shipping is already

practised and should be promoted further. The restoration and management

of cultural features will encourage a wider interest via tourism in the

area. One of the most striking features of Oostergo is the dike system

which has the potential to be promoted as a significant tourist attraction

especially for walkers and cyclists.

7.5 Cultural hertiage

The restoration and development of area specific features such as the

former shrimp catching and processing in Wierum, brick producing in

Oostrum and the old garden from Jongemastate in Rard provide the

opportunity to exploit the areas cultural heritage.

8. Sources

Marrewijk, D & A.J. Haartsen, 2002, Waddenland Het

landschap en cultureel erfgoed in de Waddenzeeregio, Ministerie van

Landbouw, Natuurbeheer en Visserij / Noordboek, Leeuwarden

Provincie Fryslan, 2006, Streekplan. Leeuwarden

|