|

1. Overview

|

Name: |

Westergo |

|

Delimitation: |

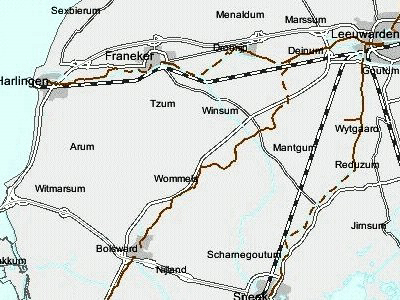

The

Westergo area is bordered to the north and west by the Wadden Sea and

the Ijsselmeer, the shallow lake formed when the Zuider Zee was closed

off from the sea by a dam. The southern and eastern boundaries are

formed by a system of dikes and a number of small lakes and waterways. |

|

Size: |

around

420 km≤ |

|

Location

- map: |

Province of Frysl‚n |

|

Origin of name: |

The north part of Frysl‚n was departed by the Middel Sea. The island on the west side is Westergo. |

|

Relationship/similarities with other cultural entities: |

Adjacent to Oostergo and

Middelzee, linked to Wieringen by the Ijsselmeer Dam. |

|

Characteristic elements and

ensembles: |

Westergo contains the

most extensive collection of dwelling mounds (terpen and wierden) in

the Netherlands. Clustered dwelling mounds and in rows; dense

groupings of water ways and former seawalls; historic field patterns,

in particular radiating out from around dwelling mounds; very open

landscape; medieval town centres and villages, Romanesque churches,

historic farming buildings, brick houses (stinzen). |

2. Geology and geography

2.1 General

The history of the area dates back to the last ice age, when the

glacial melt-waters caused rising sea-levels, in turn pushing up groundwater

levels. This caused peat to develop in a zone parallel to the coast. On the

seaward side of this peatland a line of barrier bars and islands developed.

These were subsequently breached by the sea in a number of places, breaking

them up into smaller units, forming the Wadden Sea islands. The area between

the barrier islands and the peatland was an intertidal zone of sand flats,

tidal channels and salt marshes, which were inundated by seawater twice a

day.

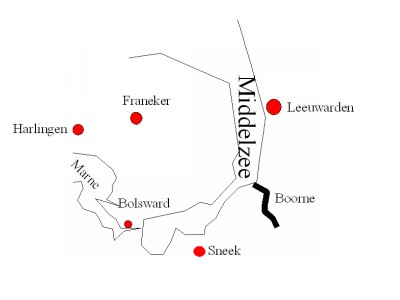

When the first inhabitants colonised the area there was a creek which

penetrated deep inland, into which the river Boorne flowed. This creek

slowly silted up and a new sound was created, the Middelzee, which served as

an estuary for the Boorne.

|

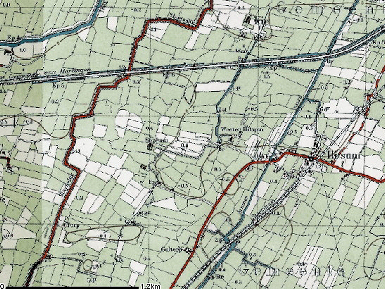

Westergo

and Middelzee with river Boorne |

Sediments were deposited along the banks of channels, forming low levees. Behind these banks were lower-lying relatively flat expanses of mudflats. To the north of Westergo a number of long salt marsh banks can be seen in the landscape running parallel to the coastline. Through the accretion of sediments the coastline shifted a number of times in a northward direction. The most southerly salt marsh bank is therefore the oldest; those lying further north are increasingly younger. The transitional zone between the sea clay landscape and the peat landscape lies to the south of Westergo.

2.2 Present landscape

Sediments were deposited along the banks of channels, forming low levees.

Behind these banks were lower-lying, relatively flat expanses of mudflats.

To the north of Westergo a number of long salt marsh banks can be seen in

the landscape running parallel to the coastline. Through this accretion of

sediments the coastline has shifted a number of times in a northward

direction. The most southerly salt marsh bank is therefore the oldest; those

lying further north are increasingly younger. The transitional zone between

the sea clay landscape and the peat landscape lies to the south of Westergo.

3. Landscape and settlement history

3.1 Prehistoric and Medieval Times

The earliest settlements were on the highest areas of land: the elevated (supratidal)

salt marsh flats in the south-east, the salt marsh banks in the north and

the levees along the Middelzee, the Marne and the smaller creeks. As soon as

enough sediment had accumulated to raise a salt marsh high enough for it to

become dry land, it appears to have been settled. However, the continuation

in rising sea levels made it necessary to further artificially raise the

ground level of these settlements. The sites were built up by adding manure

and clay sods to create dwelling mounds, called Ďterpsí.

|

| Photo: Dwelling mound (terp) with

church in Westergo |

The terp

villages in the southern part of Westergo often have an irregular field

pattern and the farms are dispersed over the area. In the northern part of

Westergo, the field pattern is more regular and rectangular. Some of these

terps were located on levees along creeks or sea inlets so that boats could

moor alongside them. These terps, which have an oblong shape with buildings

along both sides of a long road, were built for trading purposes, as opposed

to the older dwelling mounds which were constructed primarily for farmsteads.

Many terps lost their raison d?ątre when dikes were built.

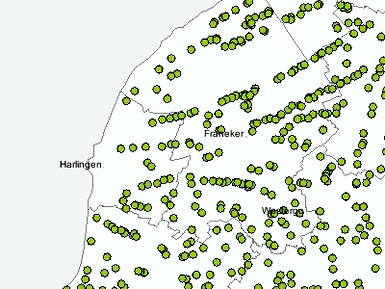

|

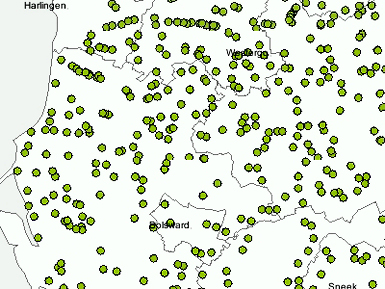

|

| Dwelling mounds in the south of

Westergo.. |

and in the north |

One of the most

striking features of the cultural history of Westergo is its dike system.

This area contains the oldest dikes in the Netherlands. The first dikes were

low and built to protect a farm or a few arable fields. In the 10th century

increasingly large areas were surrounded by ring dikes: the memmepolders, or

'mother polders'. Creeks within the enclosed ring were dammed and fitted

with sluicegates to control drainage. These mother polders then formed a

basis from which additional areas of land were enclosed by dikes, which were

built perpendicular to the older dikes around the mother polders.

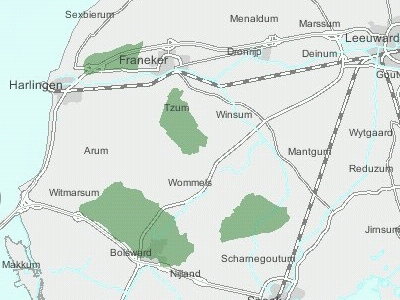

|

|

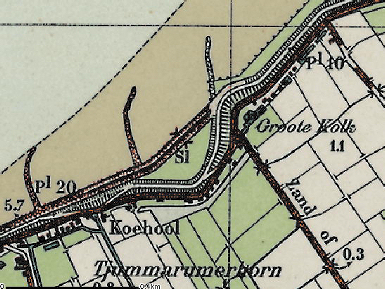

| Memmepolders or 'mother polder' |

Map of 'sleeping' or back dykes |

As this

extensive system of dikes grew, many of the earlier dikes lost their

function as sea defences and became 'sleeping dikes', or back dikes. A

sleeping dike is a flood barrier that is only needed if the primary

water-retaining structure, the sea dike, is breached. Many sleeping dikes

have fallen into disrepair over the years and have been dismantled.

Nevertheless, some remain and are still visible in the landscape, such as

the Griene Dijk and the Slachtedijk.

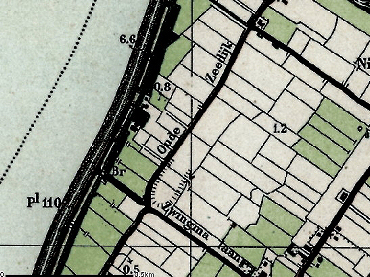

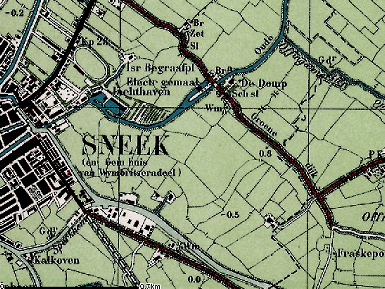

|

|

| The Griene Dijk near Sneek |

The Slachtedijk |

Clay was

excavated from other sites for the manufacture of bricks. These sites are

still marked out in the landscape by the abrupt differences in ground level

between the excavated areas and the surrounding land. 'Crown-shaped plots'

can be seen in some places. These were created by digging up the soil from

the edges of the plot depositing it in the middle to improve drainage and to

spread the risk of crop failure: in wet years the highest parts of the

arable plots produced the greatest yield; in dry years the lower areas were

more productive. In Westergo livestock farming has always been the principal

agricultural activity. Arable farming was only possible on the elevated,

drier salt marsh banks.

|

Crown

shaped plots in Westergo |

3.2 Early Modern Times

The dikes were originally built to keep out the sea, but from the 11th and

12th centuries onwards they were built to reclaim land. Before this time

parts of Westergo were regularly inundated by the sea and areas of land were

washed away. The results of these attacks on the coastline area are clearly

visible in the irregular, notched shape of the Zuider Zee coastline. In

other places the dikes were breached, leaving behind pools scoured out by

the seawater as it gushed through the breach. The dikes were repaired by

rerouting them around the pools and so in time they acquired a winding and

bendy shape.

|

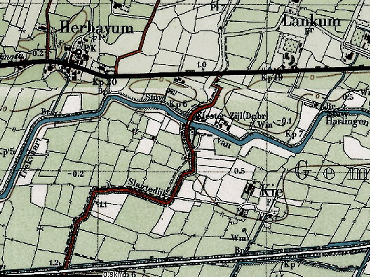

Map with

pool remnant after dyke breach (Kolk) |

The function of

the trading terp villages, which lost their open connection by water with

the Wadden Sea because of the construction of continuous dikes and

reclamation of the sea inlets, was taken over by the dam and lock villages (zijldorpen)

which grew up around the dike locks (zijlen). In total about 700 dwelling

mounds and terp villages were built in Westergo. At the end of the Late

medieval period there were five towns in Westergo: Bolsward, Workum,

Harlingen, Franeker and Hindeloopen. These towns still have their well kept,

historic town centres.

|

| Photo: Town center of Bolsward |

From the 19th

century the dwelling mounds or terps were quarried as a source of rich soil

to fertilise the arable fields. The buildings on them were often demolished

and rebuilt after the mound had been excavated. Only the steep cuttings and

fragmented remnants of the villages are still visible in the landscape,

evidence of the large-scale excavations.

Westergo has not only fought a running battle with the sea; controlling the

water inland has also presented a problem. After the construction of the

dikes, natural drainage was no longer possible, and numerous canals, such as

the Zwette, were dug. In addition natural watercourses were adapted and

sluices built. In the south-west a number of shallow lakes were reclaimed by

pumping out the water. There are three large and several small reclaimed

lakes. The regular small-scale field pattern of the larger reclaimed lakes

are in clear contrast to the surrounding irregular, rectangular field

patterns.

For a long time, water was an important means of transport. The natural

landscape contained a fine network of channels, gullies and creeks, some of

which were connected and used for drainage and navigation. In the 17th

century a network of through waterways (trekvaarten) were built. Existing

canals between the main towns were widened and deepened and towpaths

constructed along one or both sides, e.g. the Harlingertrekvaart.

|

|

| Waterways with trek paths (trekvaarten)

in Westergo |

Map of Harlingertrekvaart |

For a long time

overland transport was limited to unpaved roads on the dikes, the towpaths

and the higher parts of the salt marsh banks, but at the end of the 19th

century the country roads were supplemented with not only a rail network but

also a number of tramways and local railways. However, the tramways and

local railways soon fell into disuse when buses and lorries appeared on the

scene. The routes of many of these tramways and railway lines can still be

seen in the landscape in the form of railway embankments and the lines of

field boundaries.

An important cultural and historical feature of Westergo are the brick

houses (steenhuizen or stinsen). Originally these were single defensible

brick towers, built on mounds (stinswier) and surrounded by a moat and an

earth rampart. They initially served as places of refuge, but later on more

habitable buildings were built (zaalstinsen). The only three remaining

examples of these early brick buildings have been converted into country

houses.

|

| Photo: 'Stinswier' in Menaldum |

3.3 Modern Times

In many places the original field pattern has been altered or lost as a

result of land re-allotment schemes carried out during the 20th century. As

transport technology developed at a rapid pace during the 20th century, land

transport gained in importance at the expense of water, in spite of the

enlargement of some of the major canals connecting the harbour town

Harlingen with Leeuwarden and Groningen (van Harinxmakanaal). Many new roads

were built, but the numerous lakes and waterways outside the entity, have

always hampered the expansion of the road network. Most of the old brick

buildings (the stinsen) have been demolished to make way for farms. However,

many of the old moats have left their imprint in the landscape, and tall

trees still mark the locations of these early towers and manor houses.

4. Modern development and planning

4.1 Land use

Most of the land in Westergo is under agriculture, specializing in

dairy farming. In the northern part of Westergo near Berlikum there is a

concentration of greenhouse farming. The area was, and is, very suitable for

agriculture and planners anticipate that agriculture will remain the

principal land use activity.

|

| Photo: Greenhouse farming in

Berlikum |

4.2 Settlement development

The villages on dwelling mounds are still recognizable. Nearly all the

villages and the historical towns have new building developments on the

fringe, some of which badly fit into the old structure and landscape.

However, more attention is now paid to planning and building developments so

that they integrate better into the cultural and natural landscape.

4.3 Industry and energy

Near the old towns, particularly the harbour town of Harlingen, business and

industrial parks have developed. Between Harlingen and Franeker the strip

along the canal has been progressively infilled with industrial buildings.

In addition, the larger villages all have their own business-parks.

The open landscape, combined with the windy climate, makes Westergo a

suitable area for wind-generated energy. Early policy encouraged the

erection of individual small wind turbines near farmsteads. This policy has

changed to the encouragement of concentrations of windmills in wind-farms.

Industry was originally agriculturally-based, but this link is becoming less

important. The harbour of Harlingen is the location for a few big companies

and a gas transition plant.

4.4 Infrastructure

The highway from Leeuwarden to Harlingen and the motorway from Harlingen to

the enclosure dike (Afsluitdijk) are the most important transport links,

being the fastest connection with Amsterdam and the surrounding area. There

are two rail connections within the entity: Leeuwarden-Harlingen and

Leeuwarden-Sneek, mainly used for passenger transport. As in the past,

waterways are still important in this area, but apart from the main canal

from Leeuwarden-Harlingen, they are now particularly significant for tourist

traffic.

5. Legal and spatial planning aspects

The Legal and Spatial Planning Aspects are described in a general way, as

these are relevant to all the cultural entities in the province of FryslÉn.

Due to the scale of the cultural entities (which cover more then one

municipality), the focus is on regional policy and management. However, the

goals of the regional policy and planning strategy are taken into account by

the local sector planning policy. The regional goals and strategies are

formulated after discussion with a wide range of stakeholders and

organisations.

The regional spatial plan for the province of FryslÉn, called Streekplan, is

an important document in terms of the integrated management of landscape and

heritage. This plan presents objectives for regional and local policy, as

well as considering issues of landscape and heritage. At this moment (mid

2006) the province of FryslÉn is finalising her new regional spatial plan.

The essential qualities of the different landscapes of FryslÉn are described.

These qualities are seen as important and should be taken into account when

making planning decisions. The recognition of the essential qualities of the

landscapes, and the strengthening of them, is a primary objective. The plan

(Streekplan) emphasises the need for protection of the historic landscape

and protection by development.

6. Vulnerabilities

6.1 Spatial Planning

The open space, skyline and structure of the historical cities, towns and

villages are very vulnerable to ill informed planning for new housing and

industry. This is especially the case in the economic development zone

between Harlingen and Franker and in the cities themselves (i.e. the

extension of the harbour of Harlingen).

6.2 Settlement

The social economic situation makes industrial development a priority in the

region; specifically in the Harlingen-Franeker area, which is part of the

Westergozone, and in Leeuwarden. In the Westergozone the focus of new

housing and industrial development should be Harlingen and Franeker, both of

which should remain identifiable as separate towns. Other settlements have

room to further develop their industrial and housing estates resulting in a

loss of agricultural land. New housing also requires more space. Cultural

assets within these areas will be vulnerable to change. Many of the smaller

settlements that had been on mounds have already been lost to agricultural

improvements.

6.3 Agriculture

The historic field pattern, natural watercourses and the historic farm

buildings are vulnerable due to agriculture developments. Within the

framework of landscape core qualities there is room for large-scale

agriculture and more intensive farming (greenhouse horticulture) with the

associated innovative systems. Changes in the agricultural sector will bring

new forms of building (new building mass) and the release of valuable farm

buildings. The latter will be vulnerable to change and will require new

creative uses while conserving the building?s characteristic features.

6.4 Energy and Industry

The move towards wind power with more concentrated wind turbines may pose a

threat to below ground archaeological deposits and the visual amenity of the

wider landscape.

7. Potentials

7.1 Spatial planning

The proposed residential and industrial development should consider the

cultural heritage, both in terms of recording prior to development and

management of known sites. Within the historic core of the towns and cities

careful planning should protect the historic layout and surviving buildings.

7.2 Settlement

Many historic settlements survive and these could be promoted for tourism.

The dispersed settlement pattern of small villages and farmsteads have the

potential to be promoted via tourism for their cultural heritage.

7.3 Agriculture

Sustainable agriculture in relation to meadowland, migrating birds and

cultural historical elements contribute to the development of tourism. There

is potential for disused agricultural buildings to be used for new housing,

holiday accomodation or new small scale industrial enterprises.

7.4 Tourism

The area has clear potential for landscape and cultural history tourism. The

use of historic buildings and farmhouses for accomodation, old paths for

walking and cycling and old water ways for pleasure shipping is already

practised and should be promoted further. The restoration and management of

cultural features will encourage a wider interest via tourism in the area.

One of the most striking features of Westergo is the dike system which has

the potential to be promoted as a significant tourist attraction especially

for walkers and cyclists.

7.5 Maritime History

The specific qualities of Harlingen as a port can be used to promote the

maritime history of the area. This could be linked with the important canal

system which can be promoted via tourism.

8. Sources

Marrewijk, D & A.J. Haartsen, 2002, Waddenland Het

landschap en cultureel erfgoed in de Waddenzeeregio, Ministerie van Landbouw,

Natuurbeheer en Visserij / Noordboek, Leeuwarden

Provincie Fryslan, 2006, Streekplan. Leeuwarden

|