|

1. Overview

|

Name: |

Halligen |

|

Delimitation: |

Salt marsh islands,

neighbouring entities Pellworm, Nordstrand, Südergosharde,

Nordergosharde, Bökingharde, Amrum, Föhr |

|

Size: |

The still extant 10

Hallig islands vary from 7 ha (Habel) to 956 ha (Langeness), the

summarized salt marsh area is 2 274 ha, dispersed over a mud flat area

of roughly 20 x 30 km, also comprising the entity of Pellworm. |

|

Location

- map: |

Wadden Sea Area of North

Frisia, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany |

|

Origin of name: |

Frisian name for salt

marsh and, later, salt marsh islands without embankments with early

modern origin, meaning unknown, whereas origin of names of single

islands are known, like Hooge from high land, Langeness from long nose

or Oland from old land |

|

Relationship/similarities with other cultural entities: |

Dwelling mounds on salt

marshes were in use everywhere along the Wadden Sea coast, but

separate, other inhabited salt marsh islands (Ockholm, Galmsbüll,

Fahretoft, etc.) only existed in the Bökingharde and the northern part

of the Nordergosharde |

|

Characteristic elements and

ensembles: |

Remains of medieval settlement in adjacent mud flats |

2. Geology and geography

2.1 General

The Pleistocene basis in the underground had been eroded away by the

transgression of the North Sea since the end of the ice age and was

subsequently topped by layers of sediments and turfpeat. Marsh land and bogs

covered the area in early and high medieval times. A barrier of sand banks

and islands in the west separated this land from the open North Sea. This

protection was gradually destroyed from the 11h century on. Insular salt

marshes occupying large parts of the area were known as Strand from the end

of the 12th century on. The Hallig islands consist of salt marshes which

have formed by continuous sedimentation and erosion through over the

centuries on top of remaining bits of older salt marshes, which have

survived the catastrophic storm surge of 1362. The remains of the moraine

core protrude higher underneath the Hallig and the marsh islands than below

the adjacent mud flats and tidal inlets providing a stable basis. The layers

of turfpeat underneath the medieval marsh surface reached thicknesses from

of several tens of centimetres in the west to several meters in the east.

Most of it was cut away by humans during medieval times. Only the salt marsh

of Nordstrandischmoor has piled on top of remains of the ancient bogs.

2.2 Present landscape

Today, the large tidal inlets of Norderaue, Süderaue, Norderhever and

Heverstrom together with numerous smaller tidal canals intersect a vast

space of mud flats, spotted by the stains of the partially dry land of the

Hallig islands and the embanked marsh island of Pellworm. The largest of the

tidal inlets cut more than 20m deep into the ground more than 20m deep

whereas the salt marshes stand raise up to 2m high. The landscape of the

Hallig islands is dominated by the dwelling mounds with houses and few

protective trees on top, which can be seen from afar. Smaller tidal inlets

and often artificial canals intersect the surface. Modern, straight and

asphalted roads connect the mounds. Small harbours at the shore side provide

the connection to the main land. Today, Aall of the Hallig islands are today

protected against further erosion by stones enforcements along the edges,

yet still subject to frequent and regular flooding. Dams connect

Nordstrandischmoor, Hamburger Hallig, Oland and Langeness to the main land.

Habel, Südfall, Norderoog are not inhabited anymore and are part of the

Wadden Sea national park. Their surface is still very uneven and much more

intersected by tidal inlets. The newly gained salt marshes, especially at

the western side of Oland, distinguish notably from the irregular old salt

marshes by its regular canals, dividing the new land into square fields

intersected by parallel ditches. The whole of the Hamburger Hallig has a

similar appearance.

|

|

Tidal stream with dwelling mound in background on Hamburger Hallig.

© ALSH |

3. Landscape and settlement history

3.1 Prehistoric and Medieval Times

Some finds testify first human settlement in the area for the Young Stone

Age of around 2300 BC, but continuity can only be expected from Viking Age

Times on. Traces of settlement west of Hooge are dated as early as the 8th

century. The North Frisian Wadden Sea of this time consisted of a large

expanse of marshes and bogs, cut off by the direct influence of the North

Sea by sand barriers further west than the modern sand banks. However, aYet,

a temporary intrusion of the sea must have caused the development of salt

turfpeat along a line leading from Hooge along Nordmarsch-Langeness and

Oland into the Bökingharde. Pits as

traces of exploitation of salt

turfpeat can still be seen along this strip in the mud flats. Other

parallel ditches in the mud flats and underneath the Hallig surface display

the common practice of turfpeat cutting in order to reach the underlying

fertile clay. The turfpeat was then disposed of in the ditches. These

structures were intersected into rectangular areas by low embankments

spotted with dwelling mounds for the farms. Other mounds were larger or

combined several single mounds into a village mound. Especially the mud

flats north of Habel bore ample signs of this high medieval landscape. These

dwelling mounds were only raised from the late 12th century on as reaction

of an increasing influence from the open sea as the protective sand barriers

yielded more and more. These settlements oriented along tidal inlets, which

seemed to distribute them rather randomly. It was only then, when the area

of legendary Rungholt south-west of Südfall became inhabited. At this time

the expansive marshland area was already intersected into islands by tidal

inlets, the largest of which was called the Iisland of Strand, covering most

of the area of the Hallig and the marsh islands, while the locations of

others remain unknown.

The first embankments to protect against the rising sea can also be assigned

to the 12th century, proving that the early dwelling mounds in the area were

already protected by dikes, unlike today. When in 1362 the catastrophic

flood of the Grode Mandtränke stroke the area, it destroyed Rungholt and

large parts of the embanked marsh land, leaving behind a multitude of Hallig

islands and remnants of the older marshes.

Subsequently, the salt marshes of the Hallig islands were raised on top of

the destroyed cultivated land by sedimentation through frequent flooding.

Other parts, like the island of so-called Alt-Nordstrand or Strand was were

embanked again. The continuing loss of unprotected land often afforded

mounds to be re-built more inland. Most of the mounds on the Hallig islands

thus virtually moved with a newly heaped mound while the ancestor was left

to the waves. This process can even be tracked today as vestiges of

predecessors of some of the existing mounds still show in the adjacent mud

flats. Land use of the time and till today was has been mostly restricted to

mowing and cattle as well as and sheep breeding due to the recurrent

flooding. However, some small polders for agriculture of probably late

medieval origin, still exist on Hooge and Langeness adjacent to dwelling

mounds like Hanswarft, and are

now largely buried under the clay brought in throughout the centuries. The

land was used as common which had to be divided each spring anew among the

inhabitants in order to make up for the loss of salt marshes during the cold

season and thus remained undivided by ditches.

3.2 Early Modern Times

The storm surge of 1634 marked another important event in the landscape

history of the Wadden Sea area of North Frisia when the old island of

Alt-Nordstrand was lost to the waves and only few remaining bits of the

marshland could be embanked again in the ensuing years. Besides the marsh

islands of Pellworm and Nordstrand, it was a vestige of medieval raised bogs

that survived, heightened by accumulated clay, as Hallig island of

Nordstrandischmoor. The belfry

of the church, which survived the catastrophe, crumbled later, but the

remarkable cemetery with its

horizontal tombstones is still abiding there today. During the following

centuries, the small islands further decreased in size by the constant break

up of salt marshes along the unprotected edges. Further dwelling mounds,

erected on the comparatively high soil along the edges of the Halligen, had

to be abandoned and rebuilt farther inland. The same procedure even applied

to churches, like the one on

Gröde of late 18th century

origin, which is allegedly already the 7th reconstruction. Therefore, the

churches were simple hall constructions without belfriesy, which was were

often added as detached frame still to be seen on

Oland and

Langeness. The farms were

built in the style typical for the region, threathendthreatened by storm

surges, the so-called Uthlande style. Due to the numerous heavy floods, even

in modern times, only few have survived, especially on Langeness, like

Haus Tadsen from the 18th

century hosting a museum today.

The number of Halligen of those times itself was much greater than today.

The Beenshallig, for instance,

south of Gröde, had disappeared by the end of the 19th century.

|

|

Former Hallig island of Beenshallig south of Gröde at the end of the

19th century and present shoreline for comparison.

© LVermA-SH |

Besides the

decreasing size also the shape of the Hallig islands had changed

considerably. At the end of the 18th century,

Gröde and

Appelland, today unified, were

then two totally separate islands, the latter already uninhabited, but with

a still extant dwelling mound. Two older mounds were visible in the mud

flats west of Neuwarft on

Gröde. Wide tidal canals separated the Halligen of Nordmarsch, Langeness and

Butwehl, which are still extant, even though much narrower. The connection

to the mainland was provideds by boats fastened to small moles at larger

tidal inlets on which’s high banks the mounds were piled-up.

Habitation, as earlier, was only possible on dwelling mounds and fresh

water had to be procured by deep pools dug into the mounds, the Fethinge,

and embanked areas at the foot of the mounds, Scheetels, connected to

the Fethinge. Especially the former have survived modernisation in

comparatively large number, like on the abandoned

Pohnswarft on Hooge, but

also between modern houses as on

Ketelswarft on Langeness,

where also traces of Scheetels remained. Pools protected by ring dikes

provided fresh water even outside the dwelling mounds and are also still

extant on some occasions especially on Hooge.

a.jpg) |

|

Large tidal stream and dwelling mounds on Hallig Hooge.

© ALSH |

Farms were connected by

footpaths on the higher banks of tidal canals or the edges of the

islands, which crossed the numerous tidal inlets via movable wooden

bridges. These features have totally disappeared today. A

considerable wealth was gained from the early 17th till the end of the

18th century by some of the inhabitants through seafaring and whaling,

whereas their wivfes had to stay on the islands in order to care for the

animals. Some splendid vestiges like the

Königspesel on Hooge, a

richly ornamented room for special occasions, tell of these times.

Others fell into poverty as the constant loss of land bereft them of

their share of the land, which was not at all equally divided amongst

the islanders. The collection of wild plants and birds eggs used to be,

besides fishing and stock breeding, an important means of subsistence

for many of the inhabitants up into the 20th century.

3.3 Modern Times

Another storm tide marked the beginning of the modern time in the Halligen

area. This so-called Hallig -flood of 1825 destroyed 90% of the old

farmsteads on their mounds, leaving Südfall, where all people died,

uninhabited, except for the short episode of the so–called Hallig duchess in

the early 20th century. It was around that time when the importance of the

slowly vanishing Hallig islands as wave breaker in front of the mainland

marshes received recognition, but it took till the end of the century, when

the area belonged to the new German state, to start with the protection of

the Hallig shores with stones. This measure finally managed to stop the loss

of salt marshes but at the same time brought an end to the characteristic

transitional zone between mud flats and salt marshes, where both had merged

gradually into each other.

Since then the size of the Hallig islands has more or less stayed the same.

The wide mouths of large tidal canals, which cut through the patches of salt

marshes, were blocked by sluices during the ensuing decades, leading to

sedimentation of tidal inlets, some now not more than meandering ditches.

Thus, the small harbours

belonging to each dwelling mound before had to be substituted by common

harbours behind the new sluices, as on Gröde, or in small, protected bays,

as on Oland.

|

|

Hallig island of Nordstrandischmoor, developed on peat of the medieval

island of Strand.

© ALSH |

From around 1900,

Oland and Langeness, later also Hamburger Hallig and Nordstrandischmoor,

became connected to the mainland by dams causeways on which

narrow gauge railways have run

since the 1920ies. This offered better accessibility and has also led to

further accumulation of salt marshes.

|

|

Narrow gauge railways which connects Oland and Langeness to the

mainland since the 1920ies.

© ALSH |

The secured shoreline also finished a process during which some Hallig

islands had grown together gradually. Langeness, Nordmarsch and Buthwehl,

before separated by rather wide channels, were combined into one large

island, as well as Gröde and the salt marshes of Appelland.

|

|

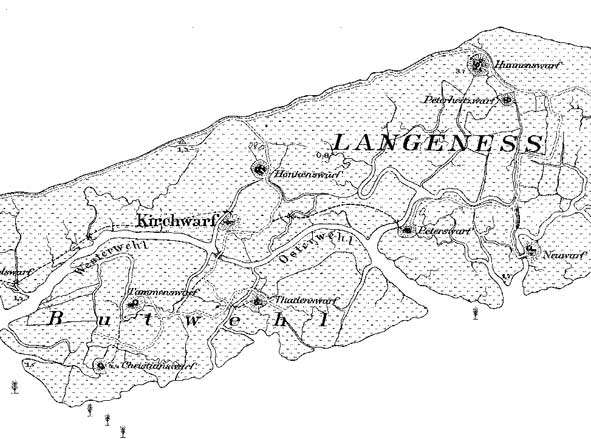

.The

division of Langeness into separate islands was still visible at the

end of the 19th century

© LVermA-SH |

The 1930ies also saw an end put to the traditional way of sharing the land

between the inhabitants every year. As the size of the islands didn’t not

decline any morefurther, this seemed unnecessary. Many ditches were dug on

Hooge by massive support of labour under the early Nazi regime in order to

divide the land, whereas on the other islands these structures remained

scarce as the shift to land devisiondivision took place later. Only on Gröde

the traditional land use has been retained till today. Land reclamation

measures around the islands have, at some places as Oland and

Nordstrandischmoor, led to new salt marshes in the west. This land is

characterised by its regular structure, originating in groynes, the parallel

fences and embankments reaching into the mud flats and made in order to

promote sedimentation, as well as the parallel ditches dug into the new salt

marshes to accelerate drainage.

4. Modern development and planning

4.1 Land use

The focus of land use has shifted very much from cattle breeding to nature

and coastal protection in recent decades. All of the small and uninhabited

Hallig islands, like Südfall, Hamburger Hallig and Norderoog are bird

sanctuaries with only an observation ward, inhabited during the warm summer

saison. Only Süderoog is used for organic agriculture, even though it is

also part of the national park.

The decline of local agriculture is mostly due to high costs of transport

and good income gained by tourism. The extensive stock breeding has always

depended largely on animals from the mainland, which are brought to the

Hallig islands only for grazing during the summer. This is still the case,

with different varying ratios of self-owned to external-owned cattle between

the islands. Damages by birds and storm floods to the pastures are being

reimbursed to the farmers. Fishery for self supply is still possible on

limited scale. Land owners also receive money as contractors to nature

protection for pastures left unused.

During the last round about 150 years the importance of the Hallig islands

for coastal protection has increased steadily. They are important as

vanguard for the mainland in order to lessen the impact of storm surges.

Therefore many islanders are at least partially employed by the state for

coastal protection works like maintaining the concrete protection of the

shores and land reclamation measures. Summer dikes around the whole islands

have reduced the number of times the islands are flooded annually, sometimes

e.g. to 2-3 times on Hooge due to its high embankmentduring the year as with

the high embankment around Hooge. Since 1976, the dwelling mounds have been

extended and sourrounded by a ring dike for protection against the

increasing flood level, which has also risen because of large embankment

projects like Beltringharder Koog in front of the mainland marshes.

Traditional highteningheightening of the mounds was not possible anymore

without disassembling the houses. This process hasn’t been finished yet and

the mound of Mittelritt/Lorenzwarft on Hooge is currently under construction.

The unique traces of medieval and early modern settlement in the mud flats,

which have been revealed over the last decades are now about to become

disguised again by increasing sedimentation in these areas.

4.2 Settlement development

The storm surge of 1962 has left many houses, especially on Hooge, in ruins.

They had to be substituted by modern constructions, which have a central,

supporting frame of concrete and a shelter in. the attic. The islands have

received fresh water and power connections with the mainland only in the

years after 1953. Naturally, the space for building is restricted to the

dwelling mounds and cannot be extended. Those buildings, which haven’t not

been substituted by modern ones, are have often been much altered

significantly and made suitableadapted forto the recent purposesrequirements.

Therefore the actual building structure is mostly influenced by tourism and,

still, protection against storm floods. Three small museums exist on

Langeness, while Hooge has two, together with a cinema, which giviprovidesng

an impressions of the storm surges. The focus of tourism differs strongly

from island to island. Hooge is the most touristic of all Hallig islands

with the highest rate of daily visitors, while Langeness, the largest of

these islands, has put more emphasis on long term tourism.

4.3 Industry and energy

Wind power generators are not allowed in this entity. No industry has ever

set foot on the Hallig islands up to now nor is it planned that it will to

do so, in the future.

4.4 Infrastructure

The traffic between the Hallig islands and the mainland is either done

performed by via ferries, mostly from the harbours of Schlüttsiel and

Dagebüll, or by via narrow gauge railways to those islands, that are

connected by a dam. The marine connection to the larger Hallig islands like

Langeness and Hooge is tide independent due to long moles reaching out to

tidal canals, while the other islands can only be reached at high tide. The

railways are only accessible at low tide. New roads had to be built to cope

with the use of cars, now paved and fitted with fixed bridges. These roads

are running straight across the islands, disregarding the traditional

courses on high banks, which often leaves them submerged in the cold seasons

for a longer time.

5. Legal and Spatial Planning Aspects

The Wadden Sea area around the Halligen and all of the uninhabited Halligen

and Süderoog are part of the Wadden Sea national park of Schleswig-Holstein,

which, in principle, aims for a natural landscape without human made aspects.

. The major part of the mud flats around the Hallig islands is

archaeological protection area. The Hallig islands of Hooge, Langeness and

Oland are also focus area for tourism, requiring specific co-ordination of

touristic building measures with the aim to keep still existing free spaces

on the dwelling mounds. Further more, Hamburger Hallig is nature protection

area, Nordstrandischmoor, Gröde, Hooge, Langeneß and Oland are also areas of

international significance for bird protection according to the Ramsar

convention and Natura 2000. Hooge is rated suitable as landscape protection

area. A recent discussion about the extension of the biospheric reservation

of the Wadden Sea to the Hallig islands has even led to a common application

of the islanders for this extension eventually, taking account of the

resistance and reluctance of many inhabitants. A model of the landscape

framework plan for the Hallig islands is focusing strongly on the natural

aspects of landscape, yet calling it cultural landscape.

6. Vulnerabilities

Much of the unique situation of the Hallig islands with their shifting and

soft borders between salt marsh and mud flats, as well as their large,

intersecting tidal inlets and major parts of the traditional culture have

been lost through modernisation and coastal protection, especially during

the last decades. Thus, at the Hanswarft on Hooge, one of the rare

freshwater collection systems, a so-called Scheetels, vanished only recently

due to an extension of the mound. Still in certain danger are elements of

the indigenous local history which are in competition with buildings and

infrastructure for the limited space on the dwelling mounds. This pressure

was largely put up by the increased focus on tourism, which, in itself, has

also changed the landscape with infrastructural measures, especially on

Hooge, the island with the highest rate of daily visitors. These

tourism-oriented actions, even if integrating cultural aspects, are often

not sufficiently co-ordinated with respective experts. Cultural heritage

still has only relatively low priority on the Halligen, contrasting its

importance for tourism. No integrated development and tourism concept thus

exists, also incorporating integrating cultural heritage. An important

attempt in the 1980ties was unfortunately dumped, which included, for

instance, proposals for adapting modern buildings with little effort to

traditional styles. More Increasing daily tourism canould expel visitors

looking for tranquillity. Historic landscape elements within the area of the

national park Wadden Sea may be threatened by extinction by measurements in

order to create a purely natural environment.

7. Potentials

The Hallig islands with their repeatedly flooded salt marshes are still an

area of a unique and impressive cultural landscape, certainly an asset. The

difficult accessibility via water, track or, sometimes, mud flats, turn out

to beis positive for those visitors seeking secluded recreation and

relaxation. Thus, the Hallig islands, especially the smaller ones, have

already a high percentage of regulars. This should naturally lead to more

sustainable, integrated forms of tourism, partially already practised, as

the limit for capacity growth for sustainable tourism is has already been

reached. Respective concepts, also taking account of the cultural historic

assets of the area as part of high quality tourist offers, are therefore

necessary, as a study of 2004 already underlines. The local use of local

products, e.g. in gastronomy, and its commercialisation still bears

potential for growth and can strengthen traditional forms of land use, which

are in return important for the the local picturelocal landscape. The Hallig

foundation was constituted in 1990 in order to promote local cultural

heritage and is therefore important for integrated concepts. The idea of a

political association to co-ordinate local development can further this

process. Besides nature trails, a culture trail can also strongly contribute

to the reception of landscape. An involvement of experts is recommended in

this respect.

8. Sources

Author: Matthias Maluck

General literature:

Vollmer, et. al. (eds.) 2001. Landscape and Cultural Heritage in the Wadden

Sea Region – Project Report. Wadden Sea Ecosystem No. 12. Common Wadden Sea

Secretariat. Wilhelmshaven, Germany.

Innenministerium des Landes Schleswig-Holstein (eds.) 2004. Regionalplan für

den Planungsraum V, Amendment File.

Ministerium für Umwelt, Natur und Forsten des Landes Schleswig-Holstein (eds.)

2002. Landschaftsrahmenplan für den Planungsraum V. Kiel.

Kunz, Panten. Die Köge Nordfrieslands (Bredstedt 1997)

Bantelmann, A, et. al. (ed.). Das große Nordfrieslandbuch (Bredstedt 2000)

Gemeinsames Wattenmeer Sekretariat (ed.) 2005. Das Wattenmeer. Theiss Verlag

Stuttgart.

M. Müller-Wille, B. Higelke, etc. (eds.), Norderhever-Projekt, Offa 66

(Neumünster 1988)

Albert Bantelmann, Rolf Kuschert, Albert Panten, Thomas Steensen. Geschichte

Nordfrieslands. (Heide 1996)

Albert Bantelmann: Nordfriesland in vorgeschichtlicher Zeit. (Bräist/Bredstedt

2003))

Chamber of agriculture Schleswig-Holstein, Machbarkeitsstudie zur

Entwicklung der Halliglandwirtschaft für die Halligen Gröde, Hooge,

Langeneß, Nordstrandischmoor und Oland (2002)

Katrin Augsburg,B. Eisenstein, Max Triphaus. Weiterentwicklung der

touristischen Organisationsstrukturen der Nordfriesischen Halligen (Study

ordered by Stiftung Nordfriesische Halligen) (2004)

U. Harth. Der Untergang der Halligen (Hamburg 1992)

M. Petersen. Die Halligen (Neumünster 1981)

Maps:

Archaeological monument record of Schleswig-Holstein and gis mapping

Lancewad data base and gis maps

Royal Prussian ordnance survey of 1879

|