|

1. Overview

|

Name: |

Nordstrand |

|

Delimitation: |

Island, neighbouring entities Pellworm, Hallig islands, Südergosharde, Eiderstedt |

|

Size: |

~50 km² |

|

Location

- map: |

Wadden Sea Area of North Frisia, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany |

|

Origin of name: |

From former island of 16th century with the same name, consisting of the two parts Nord-north and Strand-beach. |

|

Relationship/similarities with other cultural entities: |

connected with Pellworm till Early Modern Times, likewise marsh island; late medieval rows of dwelling mounds like Dithmarschen, Wiedingharde; modern polders like Nordergosharde, Dithmarschen; farm buildings like Pellworm, North Frisia; duck decoys like Netherlands, Föhr, Pellworm |

|

Characteristic elements and ensembles: |

Remains of medieval settlement in adjacent mud flats, early modern polders, dikes built on in early modern and Modern Times, farmhouses of that time, rows of medieval dwelling mounds with some vestiges of contemporary embankments |

2. Geology and geography

2.1 General

The marsh polders of Nordstrand form, together with

Pellworm, the remains of a much larger marsh area, which used to be the island of Strand and, later, Nordstrand, from which the modern name is derived. Most of which was destroyed by severe storm tides by the middle of the 17th century. Although, like Pellworm, situated on a higher Pleistocene basis than the surrounding mud flats, the area around Nordstrand had thick layers of raised bog underneath the marsh surface dug away already by the end of the middle ages.

The Hallig islands of Nordstrandischmoor in the north,

Südfall

in the west and the peninsula of Eiderstedt in the south surround Nordstrand from three directions. The deep tidal inlet of

Norderhever, which cut the medieval island of Strand gradually into half, separates Nordstrand from Pellworm further west. The former island is nowadays connected to the mainland marshes around the county town of

Husum and the polders of the

Südergosharde by a long sea dike and a road embankment.

2.2 Present landscape

The about 50 square kilometres of marshes of Nordstrand are flat and open with little relief hardly above sea level. Few trees along roads and around farmsteads, many dikes and mounds and a couple of modern wind turbines are vertical elements dominating and limiting the view besides the mostly single storey buildings, the three churches and the modern spa buildings. The polders are small scale, of irregular shape and roughly about the same size, with the exception of the large

Beltringharder

Koog, a nature sanctuary and water reservoir as connection between mainland and island. The marshland, divided by ditches into mostly rectangular but small-scale fields, is used for farming and stock breeding with dispersed singular farmsteads and houses lined up along dikes and roads missing larger clusters. Apart from the main road connecting the harbour of

Strucklahnungshörn and the mainland, there are only few and narrow roads either on former dikes or, running in more straight lines, within the polders.

|

|

Line of houses built on dike at Westen, farm mound in front.

© ALSH |

3. Landscape and settlement history

3.1 Prehistoric and Medieval Times

Disappeared raised bogs explain the pattern of settlement from late medieval times still visible today. It was well organised occupation, comparable to other settlement in boggy areas, as in Dithmarschen, resulting in long lines of dwelling mounds originally erected on parallel, narrow strips of land, along which the turf was cut. The field system had disappeared due to the storm flood of 1634, which destroyed the much larger ancestor of modern Nordstrand. The rows of dwelling mounds with single farmsteads, like in the

Alter Koog at Odenbüll and at Mitteldeich used to reach much further north and south, into the area of actual mud flats. Other relics of the time before 1634 can still be perceived. Vestiges of the medieval dikes, as well as the course of many tidal inlets, are visible or can at least be traced in the field structure of the

Trendermarscherkoog and Alter

Koog. The mud flats north and west of Nordstrand bear ample signs of medieval occupation. Especially west and south of the Hallig of Südfall, traces of groups of dwelling mounds are ascribed to the legendary settlement of

Rungholt, destroyed in the storm surge of 1362. The church of Odenbüll, first mentioned in the 13th century, is the only surviving building of that time, modernized several times during the ensuing centuries.

|

|

Church of Odenbüll.

© ALSH |

3.2 Early Modern Times

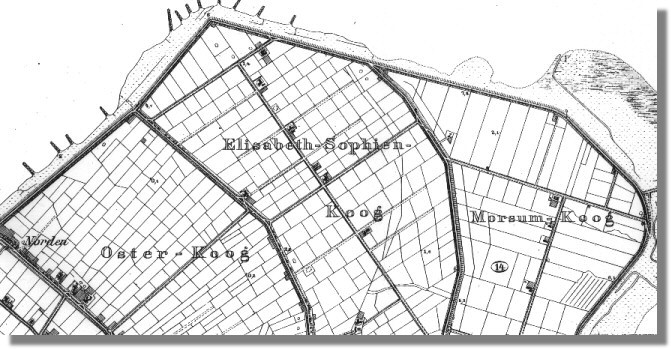

The old marshes had repeatedly been covered with new sediments after the storm surge of 1634, until 20 years later a Dutchman, based on an authorisation by the Danish king, eventually succeeded in securing remains of the earlier marshes, the Alte Koog, with a surrounding ring dike. This fostered further sedimentation and soon other polders south and east of the Alte Koog could be gained by foreign investors during the 17th century. The Trendermarschkoog still displays an irregular field pattern, stressing the course of old dikes and tidal inlets. The regular field structure of the later

Elisabeth-Sophien-Koog reveals the well organised and planned nature of land reclamation of the time and also its close resemblance to other polders in the area, especially some of the polders of the Reußenköge, which even share the same financer.

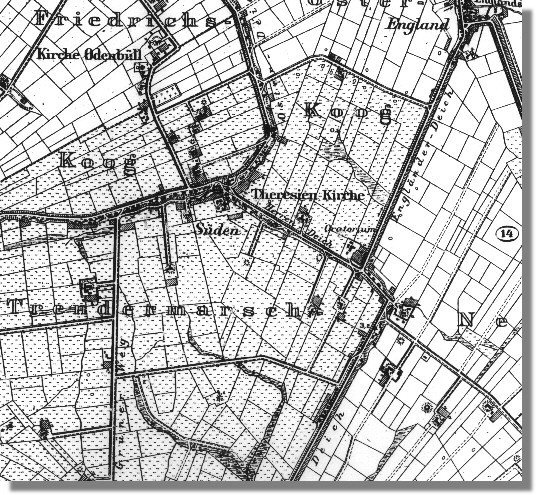

|

| Map of situation in 1879: Südendeich and Herrendeich in the middle between Alter Koog (then Freidrichskoog), Trendermarschkoog and

Elisabeth-Sophien-Koog.

©

LVermA-SH |

Many connection paths, like Grüner Weg and Armenhausstieg, between dwelling mounds have survived of the early modern infrastructure. Settlement of this time took advantage of the existing features and houses and farmsteads were built on former outer dikes, like

Osterdeich, Herrendeich or

Hamburgerdeich. The Hallig island of Südfall, situated in the mud flats full of vestiges of human settlement west of Nordstrand and formed in the years after 1362 and was later inhabited by a couple of farms on mounds. They were later destroyed by the flood of 1825, leaving the island consequently uninhabited till the early 20th century. The oldest secular buildings on Nordstrand date back to the end of the 17th century, like the Uhlande style farmhouse of In der Velden at Herrendeich, surrounded by a ditch, a feature typical for this island and the adjacent regions from where the clay for the mound was obtained. The church of

St. Theresia was already put up by Dutch immigrants, introduced for dike construction, soon after the re-embankment of the first polders. Today it hosts one of the few old-catholic parishes in Germany.

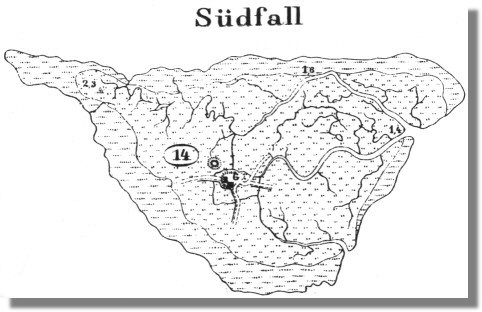

|

| Map of situation in 1879: Hallig

island of Südfall.

© LVermA-SH |

|

|

Map of situation in 1879: Difference in

field systems between early modern polders. ©

LVermA-SH |

3.3 Modern Times

The islanders set to sea by few small harbours, situated at the outer dike, like

Norderhafen, which is today equipped with a mole, or at a sluice of a tidal inlet, like

Engländerdeich, which lost its function in the end of the 19th century when it was cut off from the sea by a new polder. Süderhafen was founded as new harbour, still in use for yachts today. The new polder was embanked east of the island, encompassing rather uneven marshes, which were mainly used as pastures in the beginning. Outside the embankments, further east of the island, a small Hallig island, the

Pohnshallig, survived, protected by the island, and built on by a farmhouse with fresh water pool and a detached pool protected by a ring dike. These structures were eventually incorporated into the dike line in the early 20th century after Word War One. Divided into blocks of fields by roads and adjacent farmsteads, the former Hallig mound is still visible within the polder’s structure.

During the 19th century farming was intensified and most of the historic farmhouses, like Hof Omlandia in Morsumkoog, stem from this time. Usually they were surrounded by ditches and accompanied by gardens, of which many are still extant today, as at

Pynakers

Hof. While most of the 18th and 19th century farmhouses are of the Geesthardenhaus type, there are also few houses of the Uthlande style, more common in the northern parts of North Frisia till around 1800, like Pynakers Hof. Two

duck decoys behind the western outer dike from the early 20th century remind of a common way of bird catching at the time on the islands, originating in the Netherlands, while the neo-gothic church of

St. Knud is the most remarkable built monument around the turn of the century.

Early in the 20th century, it had already been attempted to block a tidal river between island and mainland, but only by 1936 a dam could successfully be completed, marking the beginning of the end of the situation of Nordstrand as island. Vestiges of continuous dike reinforcement and the extension of the old road system, adapting to more car traffic in the 20th century, are

clay

pits, especially in the western part of the Trendermarschkoog, and gates in old dikes, allowing them be closed again in case of flooding.

|

| Map of situation in

1879: Hallig island of Pohnshallig, the still separated from the island.

© LVermA-SH |

|

|

Duck decoy in Alter Koog.

© ALSH |

4. Modern development and planning

4.1 Land use

The gradual development of Nordstrand into a peninsular had been completed with the embankment of the Beltringharder Koog in 1987, speeding up changes of landscape. It reflects the shift of embankment policy from land reclamation to coastal protection nowadays. The interior of the polder has only been used as water reservoir and nature sanctuary, also displaying the increased awareness concerning natural assets. The Hallig of Südfall has hence also been declared as nature protection area, incorporated in the national park of the Wadden Sea area of Schleswig-Holstein. The landscape framework plan, also product of this altered thinking, identified the Trendermarschkoog as suitable for a landscape protection area. An increasing awareness towards cultural landscape assets can be tracked by the designation of the surrounding mud flats as archaeological protection area. Rural structural development has also been central for politics in the past decades, resulting in the land consolidation of Programm Nord in the 1960ies, which especially led to scale enlargement of fields and a better infrastructure of roads.

4.2 Settlement development

While the increasing importance of tourism improved the subsistence situation for the inhabitants it also changed the landscape considerably. Many new houses, especially second homes, gave some settlements a more village-like, densely built appearance, like along the central road L30, Osterdeich, Süden or Süderdeich. The spa complex of buildings introduced a modern, totally untypical architecture to the place, at the same time enriching the offers of health oriented, long term and all-year tourism. The rather uncontrolled building boom has fostered the denomination of the area as focus area for tourism in the regional spatial plan, restricting new tourist building measures considerably.

4.3 Industry and energy

As typical for coastal regions, wind power generators had been put up during the 1990ies in the polders in the north-east with a larger wind park in the

Morsumkoog and Elisabeth-Sophien-Koog and with only few wind mills at Dreisprung.

4.4 Infrastructure

The connection to the mainland resulted in a strong central road axis and especially a further rise of daily tourism due to improved accessibility. The new ferry harbour of Strucklahnungshörn in the north-west corner of Nordstrand with a large parking lot serves as main connection between Pellworm and the mainland and has led to additional traffic.

5. Legal and Spatial Planning Aspects

According to the landscape framework plan the Beltringharder Koog polder and Hallig of Südfall are nature protection areas. The Trendermarschkoog polder is suitable as landscape protection area. The mud flats are an archaeological protection area.

According to the regional spatial plan the Elisabeth-Sophien-Koog and the island in general are spas. The area of the entity is a focus area for tourism; therefore further tourist infrastructure is restricted. New wind power generators are only possible at existing locations (re-powering). Dike enforcement is planned at

Osterkoog and Alter

Koog.

Only 3 archaeological (mounds) and 3 built monuments (churches, windmill) of many important historic elements are registered on the monument list.

6. Vulnerabilities

Many of the former outer dikes are partially dug away and increasingly disguised by built on roads and houses, much larger and wider than traditionally used. Old tidal inlets can often only be discerned by the structure of the field system, like around the Schlosswarft. As most of the monuments are not protected by law they are especially prone to alteration and destruction if they will not be receive better protecting or will be integrated into planning.

Even though further growth of tourist buildings and wind parks is now restricted, concepts and actions towards more sustainable tourism and solutions concerning daily tourism and transit traffic are still missing which may lessen the attractiveness of the region in the future. For instance, enhanced building activities on old embankments could further reduce the open view into the polders and the recognition of the dikes themselves.

Nordstrand is especially stressed by car traffic due to the road connection and the ferry terminal to Pellworm. The spa buildings give a significantly alienating impression, due to their impact on the surrounding landscape.

The close arrangement of houses, especially along the central road, alters the former impression of a sparsely settled area significantly. The exceptional character of an island has been almost completely lost.

7. Potentials

Especially the Trendermarschkoog and the Alter Koog bear many historic landscape features, like fields systems, dike settlements with historic houses and connecting paths. The

Pohnshalligkoog displays 20th century land reclamation as well as vestiges of an incorporated Hallig island. A trail across the mud flats to Südfall gives also the opportunity to experience the sunken landscape and cultural remnants in the Wadden Sea. The Elisabeth-Sophien-Koog and the peninsular in general are designated as spa. A nature studies trail enhances the visitor’s awareness of landscape assets.

A general concept for sustainable tourism including cultural landscape is needed. Tourism could take further advantage of landscape and cultural assets, e.g. via an additional cultural landscape studies trail. More long term tourism and better public transport helps lessen the environmental and landscape impact of transit traffic and short term stays. The reconstruction of old connection paths has much potential to increase the experience of historic landscape and its recreational values for tourist and inhabitants. As in the local landscape plan already indicated, a mixed construction between bicycle lane and road requires less space and hence serves to protect the old dike structure.

Further tourist infrastructure altering the landscape, especially the construction of second homes, is restricted by spatial planning. New wind power generators can only be implemented at existing locations and hence are not likely to extend beyond the actual confines, to further alter views.

8. Sources

Author: Matthias Maluck

General literature:

Vollmer, et. al. (eds.) 2001. Landscape and Cultural Heritage in the Wadden Sea Region – Project Report. Wadden Sea Ecosystem No. 12.

Common Wadden Sea

Secretariat. Wilhelmshaven, Germany.

Innenministerium des Landes Schleswig-Holstein (eds.) 2004. Regionalplan für den Planungsraum V, Amendment File.

Ministerium für Umwelt, Natur und Forsten des Landes Schleswig-Holstein (eds.) 2002. Landschaftsrahmenplan für den Planungsraum V. Kiel.

Gemeinde Nordstrand. Landschaftsplan. not published.

Kunz, H. & Panten, A. 1997. Die Köge Nordfrieslands. Bredstedt.

Bantelmann, A. (ed.) 2000. Das große Nordfrieslandbuch. Bredstedt.

Johannsen, C.I. 1992. Eine reiche Hauslandschaft in ‚Nordfriesland’, no. 97. Bredstedt.

Gemeinsames Wattenmeer Sekretariat (ed.) 2005. Das Wattenmeer. Theiss Verlag Stuttgart.

Maps:

Archaeological monument record of Schleswig-Holstein and gis mapping

Lancewad data base and gis maps

Royal Prussian ordnance survey of 1879

|